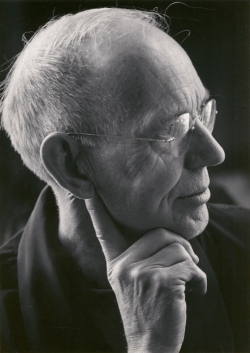

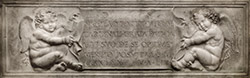

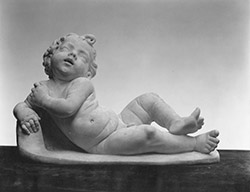

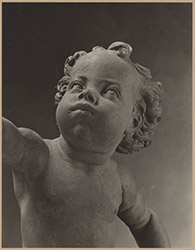

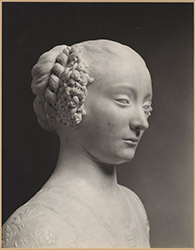

Clarence Kennedy (1892–1972), an art historian at Smith College and self-proclaimed “scholar-photographer,” revolutionized documentary art photography with subtle and illuminating details of Italian Renaissance sculpture. The limited photographic resources available for teaching art history in the early 1920s led Kennedy to pursue photography, eventually resulting in his photographic series Studies in the History and Criticism of Sculpture. Sculptors with large workshops, such as Andrea del Verrocchio (c. 1435–1488) and Desiderio da Settignano (c. 1429–1464), particularly inspired him. His exquisitely detailed photographs allowed him to compare motifs, methods, and styles to propose distinctions between the master’s hand and the work of his assistants.

Kennedy was highly regarded by both art historians and photographers. Among his closest friends were Polaroid founder Edwin Land (1909–1991) and Ansel Adams (1902–1984). Adams described Kennedy’s photos as revealing “not only his perception of the varied subjects, but his extraordinary ability to record the glow of marble and the sheen of bronze in breathtakingly beautiful prints.”

Photographing marble sculpture in situ requires a light source bright enough to illuminate the sculptures without obliterating the details and producing dark shadows. Kennedy solved this problem with his “pencil of light” method, where a bright light source was moved continuously over the object during a long exposure. He would leave the shutter of the camera open for a longer period than necessary, adding anywhere from minutes to hours to his process to allow his camera to capture the shifting light. This method would introduce desirable reflections and soften edges in order to mimic diffused daylight, resulting in what he called a “thick negative,” rich and full of detail.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)